Table of contents

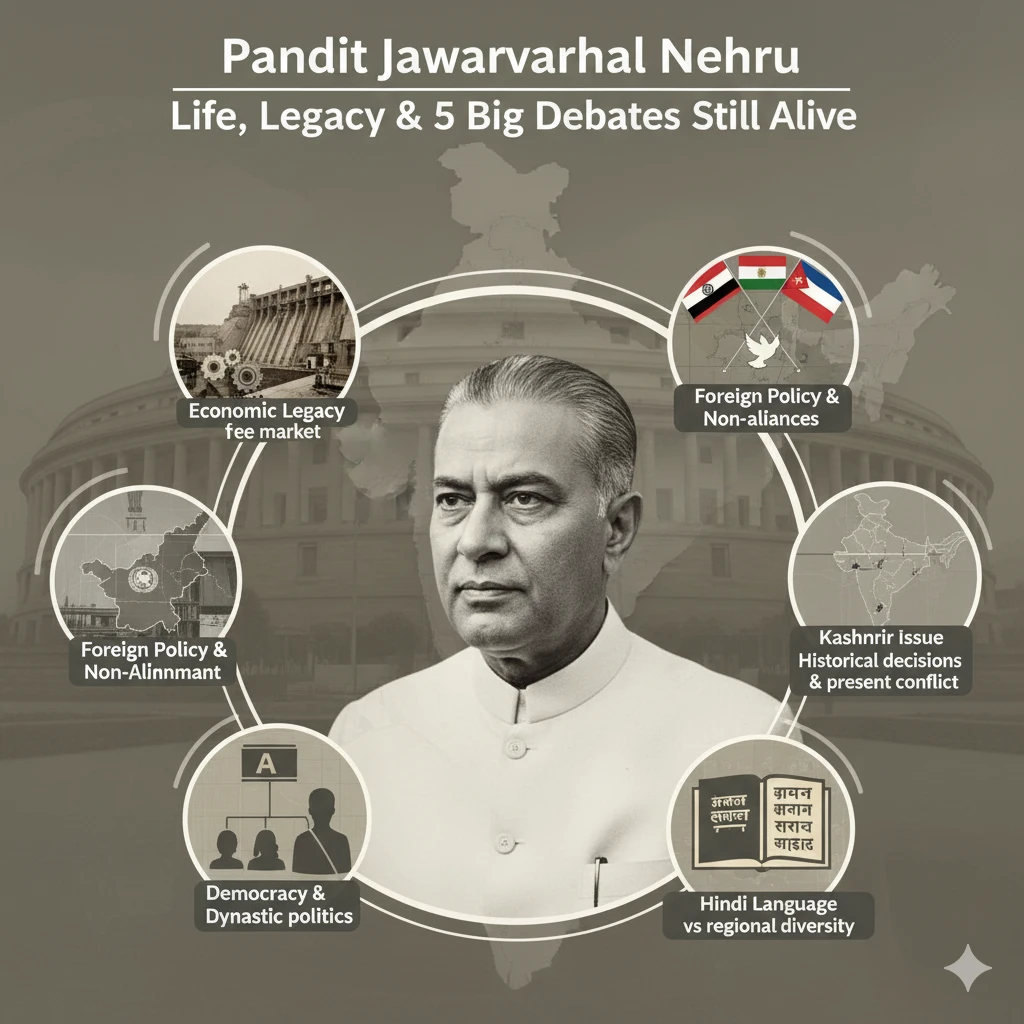

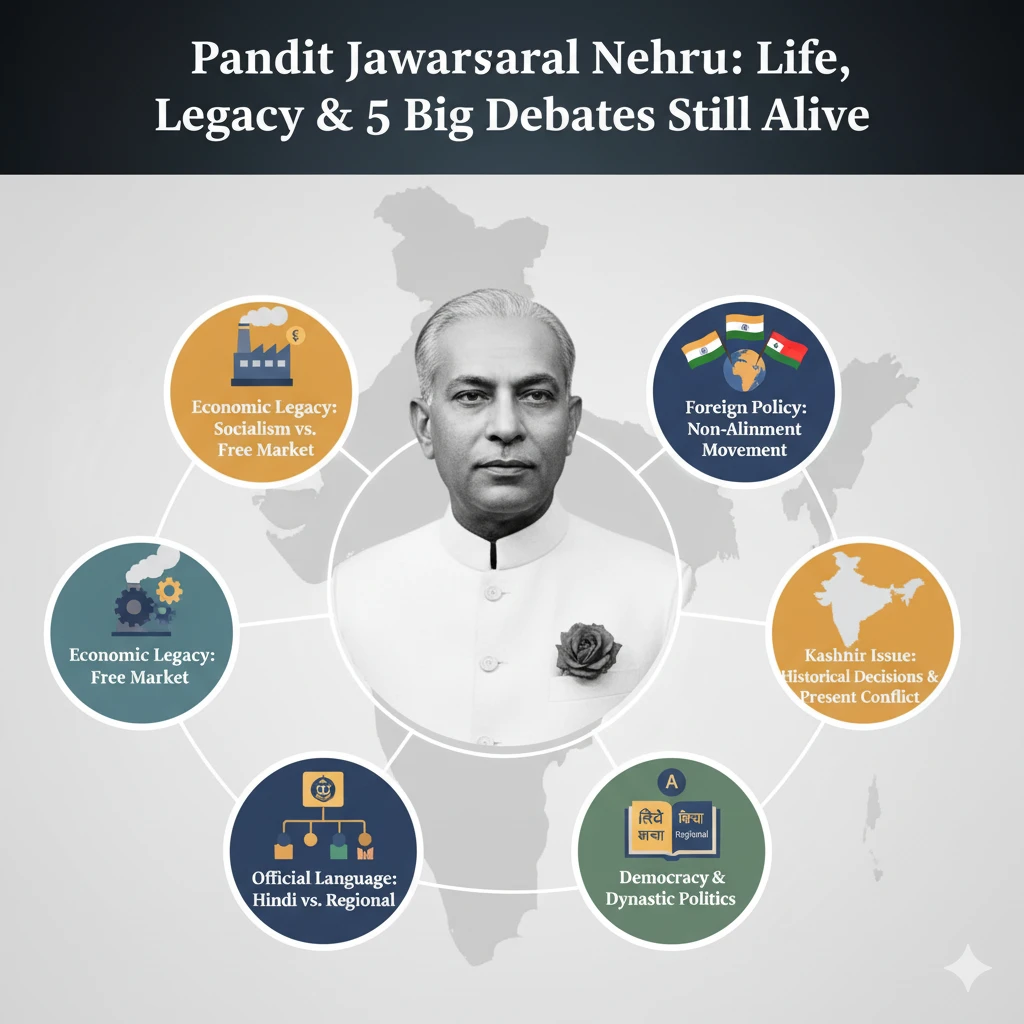

- Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru: The Good, the Bad and the Google-able

- Early Years: The Kashmiri Boy Who Hated Hindi (at First)

- Prison Diaries: The Original Instagram Stories

- The Midnight Tryst: First PM, First Problem

- Kashmir: The Signature That Never Dried

- Five-Year Plans: Soviet Inspiration, Indian Perspiration

- The China War: When Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bai Became Bye-Bye

- Love, Letters and Edwina: The Tea That Spilled

- Children’s Day: The Branding No One Planned

- Economic Legacy: License Raj or Safety Net?

- Secularism: A Word He Never Used

- Fashion & Soft Power: The Rose That Went Viral

- What Gen-Z Googles at 2 a.m.

- Quick-Fire Round: Myth vs Man

- Closing Thought: Why We Still Argue About Him

- FAQs – Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (the questions people actually type)

- FAQs – Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (the questions people actually type) Part 2

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru: The Good, the Bad and the Google-able

I still remember the first time I saw Nehru’s face outside a textbook. It was on the back of a 50-rupee note I was using to buy a packet of Parle-G in college. The shopkeeper casually said, “Woh amir aadmi tha, angrezi bolke desh chalaya.” That one line sent me down a rabbit-hole that ended in a post-grad dissertation and, now, this article. If you’ve landed here after typing “pandit jawaharlal nehru” into Google at 1 a.m., welcome.

Early Years: The Kashmiri Boy Who Hated Hindi (at First)

Born in 1889 in Allahabad’s Anand Bhavan, Nehru grew up with a silver spoon—and a governess who spoke only English. His father, Motilal, was a barrister so successful that the family swapped their horse-drawn buggy for a car in 1904, allegedly the first in the city. Young Nehru spoke Hindi only to servants; Urdu and Persian came later, almost like foreign languages. That early Anglophilia would both help and haunt him.

Sent to Harrow at 15, then Cambridge, he returned wearing Fabian-socialist ideas and a tweed jacket in the North Indian heat. His friends called him “Joe,” and for a while he dreamed of becoming an ICS officer. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919 yanked him back into India—emotionally, at least. He finally met Gandhi the same year and described the Mahatma as “a beam of light in a dark room.” Cue the entry into politics, but without the usual mass-base; Nehru’s first real constituency was still the drawing-room elite.

Prison Diaries: The Original Instagram Stories

Between 1921 and 1945 Nehru spent 3,262 days in jail. That’s almost nine years, or roughly the time it takes the average Indian government to finish a flyover. Inside, he wrote letters to his daughter that later became “Glimpses of World History”—a book still pirated on railway stations for ₹99. Jail also gave him the title “Pandit,” not because of priestly roots but as a respectful nod to his Kashmiri Brahmin surname. The tag stuck so hard that even today auto-drivers shorten it to “Panditji” without knowing why.

The Midnight Tryst: First PM, First Problem

August 15, 1947. While the world remembers the “tryst with destiny” speech, fewer know that Nehru almost missed his slot. The Constituent Assembly was scheduled to convene at 11 p.m.; he finished writing the speech at 10:58. He later told his private secretary that he “borrowed a few lines” from an earlier draft by Mountbatten’s press attaché. Plagiarism? Maybe. But in the pre-internet age, who was Ctrl+C-ing?

Becoming prime minister wasn’t a coronation. Fifteen Congress committees had voted; 12 picked Sardar Patel. Only after Gandhi gently nudged Patel to withdraw did Nehru walk in unopposed. That bit of back-room drama still fuels WhatsApp forwards claiming “Patel was the real choice.” The truth is messier: Gandhi feared Nehru would split the party if sidelined, so Patel stepped back. History, however, rarely steps back.

Kashmir: The Signature That Never Dried

On October 26, 1947, Maharaja Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession in a dimly-lit room of Jammu’s palace. Nehru accepted it on one condition: once the raiders were pushed back, “the will of the people” would decide the final status. That parenthesis became Article 370, the UN referendum promise, and every prime minister’s headache thereafter. Critics call it Nehru’s Himalayan blunder; supporters say it was the only way to keep a Muslim-majority state inside a Hindu-majority union. Either way, the ink is still wet in our collective memory.

Five-Year Plans: Soviet Inspiration, Indian Perspiration

In 1950 India’s per-capita income was ₹245 a year—less than the cost of a Domino’s pizza today. Nehru imported P.C. Mahalanobis, an Oxford-trained statistician who looked like a Bengali Einstein, to draft the First Five-Year Plan. The focus: dams, steel and science. Bhakra-Nangal, IIT Kharagpur, BARC—each project carried Nehru’s personal imprint. He loved gadgets; his bedroom had a telescope pointed at the stars and a short-wave radio tuned to BBC. Visiting a factory, he once asked a worker, “What’s your output per shift?” The worker replied, “Two litres, Panditji—but that’s lassi.”

The China War: When Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bai Became Bye-Bye

Nehru’s biggest scar came in October 1962. The Chinese army swept through Aksai Chin and Arunachal faster than a Zomato delivery. In Parliament, a teary-eyed Nehru admitted, “We were living in an artificial atmosphere of our own creation.” The phrase “forward policy” became a slur; critics accused him of trusting Zhou Enlai’s “brotherhood” rhetoric. The war shattered his international image and, more importantly, his personal equanimity. He died two years later, looking suddenly old at 74.

Love, Letters and Edwina: The Tea That Spilled

No Nehru article can dodge the Edwina Mountbatten question. The two wrote over 1,000 letters; some are locked in the Nehru Memorial Library, others vanished into private auctions. In one note he calls her “my dearest,” in another she signs off “with all my love.” Historians agree the relationship was emotional, possibly platonic. Lady Mountbatten’s daughter once told BBC, “Mummy found in Panditji the intellectual equal my father wasn’t.” Whether it crossed the line is speculation; what matters is the optics. In 1950s India, a widower PM exchanging midnight letters with the Viceroy’s wife was scandalous enough to keep rumour mills buzzing—and Google Trends alive decades later.

Children’s Day: The Branding No One Planned

Nehru’s birthday, November 14, became Children’s Day because a bunch of schoolkids in Mumbai garlanded him in 1956 and someone clicked a black-and-white photo that looked like a Hallmark card. The next year, states copied the ritual; by 1964 it was official. No parliamentary debate, no cabinet note—just pure nostalgia marketing. Today, chocolate companies owe him royalties.

Economic Legacy: License Raj or Safety Net?

The Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956 put coal, steel and telecom under state control. Critics blame Nehru for spawning the “license raj” that Indira later weaponised. Yet between 1951 and 1965 India’s GDP grew at 4.2%—respectable for a newborn republic. Poverty fell from 70% to 55%, literacy crept up from 18% to 28%. Not spectacular, but not stagnation either. The real debate: could a freer market have done better? Maybe. Could it have done worse, given the Cold-War chokehold? Also maybe. Counterfactuals are cheap; data is messy.

Secularism: A Word He Never Used

Nehru’s speeches rarely contained the Hindi word “dharm-nirpeksh.” He preferred “sarva-dharma-sambhav”—equal respect for all faiths. Yet he vetoed President Rajendra Prasad’s plan to attend the Somnath temple reconstruction in 1951, arguing state and religion must stay separate. The move angered many Hindus, pleased minorities, and confused the majority who just wanted jobs. In 2023, that same tussle plays out every time a CM tweets a temple visit. Nehru didn’t invent secularism; he just Indianised it, warts and all.

Fashion & Soft Power: The Rose That Went Viral

The red rose pinned to his achkan wasn’t a stylist’s idea. In 1936 he saw a dew-laden rose in a Srinagar garden and told a reporter, “It reminds me that beauty exists even in struggle.” Photographers loved the visual; soon every schoolboy was doodling a rose next to a bespectacled face. The brand value? Priceless. When Indira later wore a white sari with a black border, she was borrowing from the same playbook—personal symbolism as political messaging.

What Gen-Z Googles at 2 a.m.

Open an incognito tab and type “nehru.” Auto-complete spits out: “nehru jacket,” “nehru children,” “nehru modi debate,” “nehru death reason.” Each query is a rabbit-hole. The jacket? A hip-length bandhgala popularised by The Beatles, now sold by Zara for ₹4,000. Children? Nehru had one biological child, Indira, but informally adopted a policy of “every Indian child is mine.” Death? Not cardiac arrest alone; some books claim a broken heart post-China war. The Modi debate? That’s a daily Twitter mud-wrestle we’ll park for another article.

Quick-Fire Round: Myth vs Man

- Myth: Nehru banned the RSS.

Fact: He banned it once, February 1948, after Gandhi’s assassination; lifted the ban July 1949 on the condition that the RSS write a constitution. - Myth: He hated capitalism.

Fact: He invited J.R.D. Tata to head the National Planning Commission and personally inaugurated the Bhilai steel plant with British collaboration. - Myth: He was anti-religion.

Fact: He donated money from his Nobel Peace Prize nomination fund (he never won) to rebuild the ancient Nalanda university ruins, a Buddhist site. - Myth: He died penniless.

Fact: He left behind ₹7,000 in a savings account and a house that later became the Nehru Memorial—hardly rich by today’s standards, but not penniless.

Closing Thought: Why We Still Argue About Him

Nehru is like that family elder whose WhatsApp forwards you can’t delete. You didn’t choose him, but he’s on every group. Some share his “tryst with destiny” speech on Independence Day; others meme him with China war jokes. Both reactions prove one thing—he’s still the reference point. You measure modern India against him: our GDP, our secularism, our foreign policy, even our rose emojis. Love him, loathe him, you can’t mute him. And as long as Google auto-complete exists, nobody will.

FAQs – Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (the questions people actually type)

No. He was born in Anand Bhavan, Allahabad (now Prayagraj), on 14 Nov 1889. His family were Kashmiri Pandits who had settled in the United Provinces generations earlier.

After he died in 1964, Parliament moved his birthday (14 Nov) to National Children’s Day because of his famous affection for kids. The rose-in-hand photo with schoolchildren cemented the idea.

Yes—more than 200. They were later published as “Letters from a Father to His Daughter” and still sell on Amazon for ₹85.

3,262 days spread over nine terms between 1921 and 1945. That’s roughly nine years—longer than most people spend in college.

The wife of India’s last Viceroy. She and Nehru exchanged over 1,000 letters. Historians agree the bond was deep and emotional; whether it was romantic is still debated.

Not exactly. Congress provincial committees preferred Patel 12-to-1, but Gandhi felt Nehru’s mass appeal was essential to keep the party united. Patel agreed to withdraw.

He hoped international pressure would force Pakistan to withdraw tribal invaders. Critics say it internationalised a domestic issue; supporters argue it bought time to save Srinagar.

A hip-length, collarless coat popularised by Nehru in the 1940s-50s. The Beatles wore it, Zara still sells it, and it has zero connection to traditional Kashmiri attire.

He opposed mixing religion with statecraft but funded restoration of Buddhist sites like Sanchi and Nalanda. His personal belief is best described as agnostic with cultural Hindu habits.

Official cause: heart attack on 27 May 1964. Close aides say the 1962 China war defeat and subsequent stroke had already weakened him physically and mentally.

FAQs – Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (the questions people actually type) Part 2

No. The RSS was banned once (Feb 1948-Jul 1949) after Gandhi’s assassination; the restriction was lifted once the organisation wrote a formal constitution pledging loyalty to the Indian Constitution.

The mixed-economy model: massive public-sector dams, steel plants and the IIT network. It delivered 4% annual growth in the 1950s but also sowed the “license raj” that later slowed business.

Just one house—Anand Bhavan—which he donated to the nation. His savings account held ₹7,000; royalties from his books went to the Prime Minister’s National Relief Fund.

They cite his “forward policy” of setting posts behind Chinese lines without matching military build-up. Nehru himself admitted in Parliament, “We were living in a world of our own imagination.”

Digitised archives at the Nehru Memorial Museum & Library (nmml.gov.in) and the Parliament of India website. Both are free, no sign-up needed.